Programming with the GoAt Eclipse plugin

We developed the Eclipse plugin to give the user the power to describe CAS interaction schemes in a language agnostic way. Another point we stress is that even the interaction scheme is independent from the message exchange infrastructure.

When launching the plugin, you get this screen

On the left, you have the set of projects that are in your workspace. In GoAt, a project is a description of your system in term of components, interaction and infrastructure. You can create a new project by right-clicking on the Project Explorer, New > Project… . Among the wizards, choose Goat > Goat project, then click Next and give it a name (e.g. “a_project”).

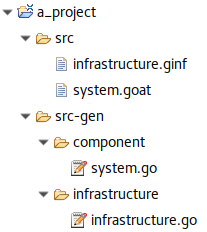

Now, in the Project Explorer, expand the project tree.

The src directory contains two types of files: .ginf and .goat. .ginf files describe the communication infrastructure between the component (that is, how the messages are delivered), while .goat files describe the components of the system and how they interact. We require the infrastructure details to be kept away from the components because:

- we want to stress that the component behaviour is independent from how the messages are delivered;

- they might be developed by different users: the system administrator configures the infrastructure, and the programmer develops the components.

The only linking point is the infrastructure statement in .goat files which states that the components described inside use a specific named infrastructure.

The src-gen directory contains the go code generated from the code generation procedure that corresponds to the infrastructure(s) and component(s) described in the project. When a system is run, the plugin calls Go and runs the files inside this directory. Note that component and infrastructure files are kept separated.

Running a project

This section describes how to run a GoAt project. To do this, we provide a simple system just to see some interaction. Next sections describe the specification language.

Open infrastructure.ginf and paste this code, then save the file (CTRL+S):

singleserver infr {

server : "127.0.0.1:17654"

}

Open system.goat and paste this code, then save the file:

infrastructure infr

process P {

send{"hello world"} @ (true);

}

process Q {

receive(true){x} print("Got $x$");

}

component {} : P

component {} : Q

This code describes:

- a centralised infrastructure whose address is

127.0.0.1:17654; - a system made of two components, where one sends

hello worldto the other, using the infrastructure.

The plugin offers an editor with syntax higlighting and error checking. Try, for example, to change send to sed and you will get an error.

Right-click on the project, then click Run As > Run System. Now you get two consoles in the Console view, and you can switch between them with this drop-down menu  . The consoles contain the standard output (in black) and standard error (in red) of the system and of the infrastructure. Open the

. The consoles contain the standard output (in black) and standard error (in red) of the system and of the infrastructure. Open the system.goat console. It contains Got hello world. The component whose process is P has sent the hello world message to every component (true predicate). The component whose process is Q received the message and printed it out with the print directive. Since both the components terminated, also the system terminated. Now open the infrastructure.ginf console. The only output line is Started, to singal that the infrastructure started. The infrastructure is still running, waiting for new messages. You can stop it by pressing the Terminate button ( ). Before closing the plugin or running other systems, remember to stop all running infrastructure and components as they might interefere with the new runs.

). Before closing the plugin or running other systems, remember to stop all running infrastructure and components as they might interefere with the new runs.

Programming components

This section describes how to program the components in .goat files. Components are the parts of the system that interact in order to attain a global behaviour. The first part describes the main constructs that can be used; the remainder describes some patterns that recur during the development.

GoAt constructs

A .goat file begins with infrastructure infr where infr is the name of an infrastructure declared in the project. This statement says that the components described in this file are to be attached to the infrastructure infr.

The remainder of the file is a set of process, environment, component and function declarations.

- The processes represent the dynamic behaviour of components. They can send and/or receive mesages, access the component environment and use local attributes. Local attributes are not shared between processes, even if they are on the same component.

- The environment is a map between names (called component attributes) and values. The environment represent the state of a component. The environment is not shared between components, but all processes running on a component can read and write over it.

- The component is the pair of an environment and a process. Components interact between each other by message passing according to their state.

- Functions are used to compute values, that can be sent with messages, saved in attributes or used in predicates.

Process

A process is defined as

process P {

...statement 1...

...statement 2...

...statement n...

}

P is the name of the process. The statements are executed one after another, and when the last statement terminates the process terminates. The available statements are: send, receive, waitfor, set, if, call, spawn and loop.

It is also possible to define a process as the parallel composition of a set of processes, using:

process P = P1 | P2 | ... | Pn

send

The send statement is used to send a message. Its syntax is

send{expr1, expr2, ..., exprn} @ (pred) [attr1 := expr_a1, attr2 := expr_a2, ..., attrm := expr_am] print("output");

This statement sends the message (the tuple {expr1, expr2, ..., exprn}) to any component satisfying the predicate pred. Any message received while a process is sending is discarded, i.e. subsequent receives from the same process will not perceive those messages. In the expressions expr_i it is possible to use component attributes and local attributes. They can be accessed by prepending comp. or proc. to the name of the attribute. Each component but the sender, evaluates the pred predicate (i.e. a boolean expression): the message is accepted if and only if pred evaluates to true. pred can refer to receiver attributes by prepending receiver. to its name.

Note 1: Make sure that the component or local attributes you are referring exist. Otherwise, the component will crash at runtime.

Note 2:

predmay refer to receiver attributes that do not exist on other component. In that case, the attribute is considered to be neither equal, greater, littler, different than anything and neither true or false.For example, assuming that the receiver does not have the attribute x, the predicate

receiver.x == v || receiver.x != vis always false no matter which is the value of v. Otherwise, if attribute x is defined and has the same type of v, the predicate is always true.

The [attr1 := expr_a1, attr2 := expr_a2, ..., attrm := expr_am] part updates the component or local attributes to the evaluation of the corresponding expressions. This part can be omitted if the attributes do not change.

print("output") prints on the standard output the specified string after sending the message. Inside the string, it is possible to get the value of a local attribute (e.g. x) by writing its name between dollar signs (e.g. $x$). It is possible to get the value of a component attribute (e.g. a) by writing its name prefixed with comp. between dollar signs (e.g. $comp.a$). Even this part is optional, and if omitted after the send nothing will be printed out.

Note 3: The print part is to be used only for debugging purpouses. The printing format might change in the future.

receive

The receive statement is used to receive a message. It has two possible syntaxes.

The first syntax is:

receive (pred) {lattr1, lattr2, ..., lattrn} [attr1 := expr1, attr2 := expr2, ..., attrm := exprm] print ("output");

This statement accepts the first message that satisfies the pred predicate and has exactly n parts. Then, the part i is assigned to the local attribute attri. If the received message does not can not be accepted, it is discarded and the process waits for another message.

The [attr1 := expr1, attr2 := expr2, ..., attrm := exprm] part updates the component or local attributes to the evaluation of the corresponding expressions. It is possible to access component attributes by prepending comp. to the name of the attribute. It is possible to access local attributes by prepending proc. to the name of the attribute. This part can be omitted if the attributes do not change.

Note: Make sure that the component or local attributes you are referring in

exprs exist. Otherwise, the component will crash at runtime.

Tip: You can set component attributes to received values by using the update part: first save the message part in a fresh local attribute, then copy it in the component attribute. For example,

receive(true){x}[comp.x := proc.x];saves in the component attribute x the content of the first message received that has only one part.

print("output") prints on the standard output the specified string after receiving a suitable message. Inside the string, it is possible to get the value of a local attribute (e.g. x) by writing its name between dollar signs (e.g. $x$). It is possible to get the value of a component attribute (e.g. a) by writing its name prefixed with comp. between dollar signs (e.g. $comp.a$). Even this part is optional, and if omitted after the reception nothing will be printed out.

The other syntax is:

receive {

case (pred1) {lattr1_1, lattr1_2, ..., lattr1_n1} [attr1_1 := expr1_1, attr1_2 := expr1_2, ..., attr1_m := expr1_m1] print ("output1"): {

... statements1 ...

}

case (pred2) {lattr2_1, lattr2_2, ..., lattr2_n2} [attr2_1 := expr2_1, attr2_2 := expr2_2, ..., attr2_l := expr2_m2] print ("output2"): {

... statements2 ...

}

...

}

This statement accepts the first message that satisfies predj where predj is a predicate stated in one of the cases. If more than one is satisfied, then we consider the one with the lowest j. It is similar to a switch ... case statement used in many imperative languages. Then, it saves the message parts, updates the environment and prints a message as explained for the first syntax of receive. After, the statements statementsj are executed. If the received message does not satisfy any of the predicates, it is discarded and the process waits for another message.

waitfor

The waitfor statement waits until a condition is satisfied or a period of time is elapsed. Any message received while waiting is discarded.

Its syntax is:

waitfor(cond)[attr1 := expr1, attr2 := expr2, ..., attrm := exprm] print ("output");

cond can be:

- a predicate over local and component attributes, accessed prepending

proc.orcomp.to the name of the attribute - an integer constant stating the number of milliseconds to wait

The [attr1 := expr1, attr2 := expr2, ..., attrm := exprm] part updates the component or local attributes to the evaluation of the corresponding expressions. It is possible to access component attributes by prepending comp. to the name of the attribute. It is possible to access local attributes by prepending proc. to the name of the attribute. This part can be omitted if the attributes do not change.

Note: Make sure that the component or local attributes you are referring in

exprs exist. Otherwise, the component will crash at runtime.

print("output") prints on the standard output the specified string after waiting. Inside the string, it is possible to get the value of a local attribute (e.g. x) by writing its name between dollar signs (e.g. $x$). It is possible to get the value of a component attribute (e.g. a) by writing its name prefixed with comp. between dollar signs (e.g. $comp.a$). Even this part is optional, and if omitted nothing will be printed out.

set

The set statement updates the set of local and global attributes.

Its syntax is:

set [attr1 := expr1, attr2 := expr2, ..., attrm := exprm] print ("output");

The [attr1 := expr1, attr2 := expr2, ..., attrm := exprm] part updates the component or local attributes to the evaluation of the corresponding expressions. It is possible to access component attributes by prepending comp. to the name of the attribute. It is possible to access local attributes by prepending proc. to the name of the attribute. This part can be omitted if the attributes do not change.

Note: Make sure that the component or local attributes you are referring in

exprs exist. Otherwise, the component will crash at runtime.

print("output") prints on the standard output the specified string after the update. Inside the string, it is possible to get the value of a local attribute (e.g. x) by writing its name between dollar signs (e.g. $x$). It is possible to get the value of a component attribute (e.g. a) by writing its name prefixed with comp. between dollar signs (e.g. $comp.a$). Even this part is optional, and if omitted nothing will be printed out.

loop

The loop statement repeats endlessly a sequence of statements. Its syntax is:

loop {

... statements to repeat ...

}

if

The if statement executes different codes according to the state of the attributes. Its syntax is:

if (cond1) {

send/receive/set

...statements1...

} else if (cond2) {

send/receive/set

...statements2...

}

....

else {

send/receive/set

...statements_e...

}

It is similar to the if ... else if ... else construct in imperative languages. It considers the first branch whose condition is satisfied; then it tries to execure the first statement. Depending on first statement of the block:

- if it is a

send, it sends the message and then executes the rest of the block; - if it is a

receiveand the first message received is accepted, it executes the rest of the block; - if it is a

receiveand the first message received is not accepted, it waits for a change in the environment or a new message and retries the whole if statement; - if it is a

set, it updates the environment and then executes the rest of the block.

If none of the condition are satisfied, it executes the else block if available, otherwise it waits for a change in the environment or a new message and retries the whole if statement.

Tip: in a block, if you do not want to change the environment nor send or receive messages, you can use

set;as the first statement. Note that thesetstatement discards messages during its execution.

Note: Unlike (many) imperative languages where an

ifwithout anelsewhose condition is not satisfied behaves as having an empty else branch, in GoAt blocks the execution of the process. The classical behaviour is re-establish by usingelse{ set; }. Pay attention that thesetstatement discards messages during its execution.

call

The call statement executes the code of another process. Its syntax is:

call(P)

P is the name of a process. P will inherit the set of local attributes of the current process. The control will not return to the current process, so any statements written after call will not be executed.

spawn

The spawn statement ceates a new process that executes the code of some process. Its syntax is:

spawn(P)

P is the name of a process. P will inherit a copy of the set of local attributes of the current process. The current process and the process just created will run concurrently on the same component. As any other pair of process, they share component attributes but not the set of local attributes.

It is also possible to spawn a process once a message is received. To do this, the syntax of the receive is:

receive (pred) {lattr1, lattr2, ..., lattrn} [attr1 := expr1, attr2 := expr2, ..., attrm := exprm] spawn(P) print ("output");

or

receive {

case (pred1) {lattr1_1, lattr1_2, ..., lattr1_n1} [attr1_1 := expr1_1, attr1_2 := expr1_2, ..., attr1_m := expr1_m1] spawn(P1) print ("output1"): {

... statements1 ...

}

case (pred2) {lattr2_1, lattr2_2, ..., lattr2_n2} [attr2_1 := expr2_1, attr2_2 := expr2_2, ..., attr2_l := expr2_m2] spawn(P2) print ("output2"): {

... statements2 ...

}

...

}

The spawn clause is entirely optional, and it might be present on some/all/none of the cases.

Environment

The environment is defined as:

environment E {

attr := immediate,

attr := immediate,

....

attr := immediate

}

Component

The component is defined as:

component E : P

E is an environment; it is a name of a defined environment or it can be replaced by the set of attributes and values. P is the name of a process or the parallel composition of a set of processes or a process definition.

Functions and expressions

In attribute updates, predicates and message parts, it is possible to use values that depend on attributes. To describe them it is possible to use an expression language. The expressions are typed, and three types are defined: integers (int), booleans (bool) and strings (string). The operation defined are:

| Operators | Applicable types | Return type |

|---|---|---|

<, <=, >, >= |

int, string |

bool |

==, != |

int, string, bool |

bool |

&& , || |

bool |

bool |

+, -, *, /, % |

int |

int |

++ (concatenation) |

string |

string |

There is also the unary operator ! that negates a bool.

It is also possible to define functions, to be used in expressions. The function syntax is:

function type name (type param1, type param2, ...) {

... function statements ...

}

The avaliable statements are:

- variable declaration:

var name = exprwhere the variable’s type is inferred fromexpr; - assignment to variables:

name = expr; - return:

return expr; - condition:

if ... else if ... elsewhose behavior is the standard one.

Inside function is possible to use expressions that refer to parameters or variables. It is also possible to use function calls (even recursive ones).

Defining infrastructures

This section describes how to define infrastructure in .ginf files. Infrastructures are what make the components actually communicate. Their role is to distribute messages from a component to all the others. There are four types of infrastructures: centralized, cluster, ring and tree. The syntax of a .ginf file is:

infrastructure_type name {

param : value,

param : value,

...

param : value

}

The following table contains the list of parameters.

| Infrastructure | infrastructure_type |

param |

value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centralized | singleserver |

server |

Address and port of the server, e.g. "127.0.0.1:14000" |

timeout |

Number of milliseconds without any interaction after which the server terminates. Optional. If not specified, it means infinite. | ||

| Cluster | cluster |

message_queue |

Address and port of the message queue, e.g. "127.0.0.1:14000". |

registration |

Address and port of the registration node, e.g. "127.0.0.1:14000". | ||

mid_assigner |

Address and port of the node that assigns fresh message ids, e.g. "127.0.0.1:14000". | ||

nodes |

List of serving nodes in the cluster, e.g. ["127.0.0.1:14000", "127.0.0.1:14001"] | ||

| Ring | ring |

registration |

Address and port of the registration node, e.g. "127.0.0.1:14000". |

mid_assigner |

Address and port of the node that assigns fresh message ids, e.g. "127.0.0.1:14000". | ||

nodes |

List of serving nodes in the ring in order, e.g. ["127.0.0.1:14000", "127.0.0.1:14001"]. The i th node's next is the (i+1) th in the list. The last node's next is the first one. | ||

| Tree | tree |

registration |

Address and port of the registration node, e.g. "127.0.0.1:14000". |

nodes |

Depth-first visit of the tree. E.g. "127.0.0.1:14000" [ "127.0.0.1:14001" [ "127.0.0.1:14002", "127.0.0.1:14003"], "127.0.0.1:14004" ], where the root is "127.0.0.1:14000" and its children are "127.0.0.1:14001" and "127.0.0.1:14004". |

An Example: Stable Allocation in Content Delivery Network

This case study is based on the distributed stable allocation algorithm adopted by Akamai’s Content Delivery Network (CDN) See.

Akamai’s CDN is one of the largest distributed systems in the world. It has currently over 170,000 server located in over 1300 networks in 102 countries and serves 15-30% of all Web traffic. To avoid dealing with billions of clients individually, Akamai divides the clients of the global internet into groups, called map units each having a specific demand, based on their locations and traffic types. Also content servers are grouped into clusters, and each cluster is rated according to its capacity, latency, etc. Map units prefer highly rated clusters while clusters prefer low demand map units. The goal of global load balancing is to assign map units to clusters such that preferences are accounted for and constraints are met.

The allocation algorithm of Akamai is a slight variant of the original Stable Marriage Problem (SMP), see. The goal of the original algorithm is to find a stable matching between two equally sized sets of elements given an ordering of preferences of each element of the two sets. Each element in one set has to be paired to an element in the opposite set in such a way that there are no two elements of different pairs which both would rather have each other than their current partners. When there are no such pairs of elements, the set of pairs is deemed stable.

The variant of Akamai allows (1) more map units to be assigned to a single cluster and (2) map units to rank only the top dozen, or so, clusters that are likely to provide good performance. The first feature is a typical generalisation of the original SMP, while the second is a mere simplification of the problem. Implementing these features in GoAt does not pose any challenge, but it would make the example more verbose. Furthermore, these features do not add much to the original SMP; they still require map units and clusters to have predefined lists of preferences such that only ranked elements can participate in the algorithm. Obviously, this implies that one cannot take advantage of dynamic creation of new clusters.

We consider a more interesting variant of SMP that is better suited for the dynamicity of CDN. In this variant, the arrival of new clusters is considered, it is not required that elements know each other, and no predefined preference list is assumed. Notice that, in these settings, point-to-point interaction is not possible because elements are not aware of each other and the choice of implicit multicast is crucial. Indeed, in our variant, elements express their interests in potential partners by relying on their attributes rather than on their identities. In essence, an element of one set communicates with elements of the opposite set using predicates. Two parties that agree on some predicates form a pair, otherwise they keep looking for better partners. A pair splits only if one of its elements can find a better partner willing to accept its offer. In this way, preferences are represented as predicates over the values of some attributes of the interacting partners.

In this scenario, we consider the values of attributes demand, for a map unit, and rating, for a cluster, as a means to derive the interaction. For simplicity, these attributes can take two different values: high (H) and low (L). An element in the system can be either a Unit or a Cluster. Units start the protocol by communicating with clusters in the quest of

finding an

element that satisfies their highest expectations. If no cluster accepts the offer, a unit lowers its expectations and proposes again until a partner is found. Clusters are always willing to accept proposals from any unit that enhances their levels of satisfaction. In case of a new arrival, some pairs of elements might dissolve if the new arrival enhances their levels of satisfaction. This means that not all pairs in the system are required to split on new arrivals; only those interested will do so. The system level goal (the emergent behaviour) is to construct a set of stable pairs from elements of different types by combining the behaviour of individual elements in the system through message passing. Mathematically speaking, the problem consists of computing a function at the system level by combining individual element behaviours, without relying on a centralised control.

Notice that since map units initiate the interaction, the solution is a map-unit-optimal, as proved in the original SMP, which is a property that fits with the CDN’s goal of maximising performance for clients.

Allowing new arrivals is crucial to guarantee scalability and open-endedness while communicating based on predicates rather than on identities or ranks is crucial to deal with anonymity.

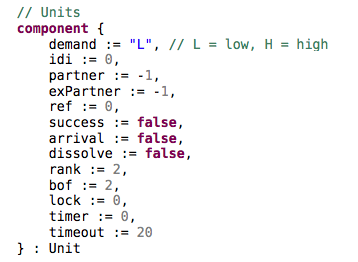

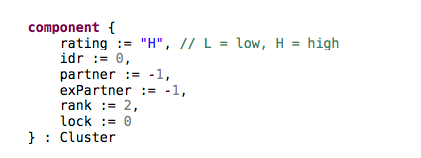

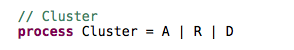

The system in our attribute-based scenario can be modelled in Goat as the parallel composition of existing units and clusters. Notice that units and clusters interact in a distributed setting without any centralised control. Each element is represented as a \Goat component. Below we show an example of a Unit and a Cluster:

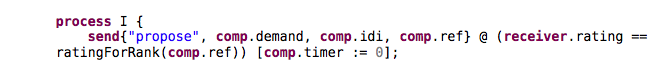

A Fragment of the Unit behavior where a unit propose to be paired to a cluster with high rating is shown below:

Notice that a unit can have “l” number of proposal variants by relying on non-determinism and the value of attribute ref. The unit can start with high expectation and keeps lowering until it is paired into a Cluster.

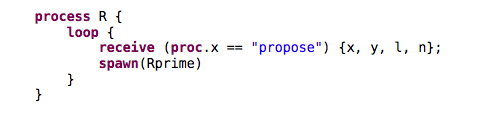

A Fragment of the Cluster behavior wehre a cluster recieve a proposal is shown below:

Notice that the cluster can receive any proposal and only accept proposal that enhances its satisfaction level.

In the original SMP, the authors showed that their algorithm terminates with a matching that is stable after no more than n^2 proposals, where n is the number of proposing elements, i.e., the algorithm has O(n^2) worst-case complexity. In our variant, it should be clear that the worst case complexity is also O(n^2) even after relaxing the assumptions of the original algorithm, i.e., no predefined preference lists and components are not aware of the existence of each other, so point-to-point communication is not possible. Interestingly, the complexity is still quadratic even if we consider a blind broadcast mechanism where proposals are sent to all components in the system except for the sender unit. In this way, for $n$-units, $n$-clusters, and l-preferences of a unit where l represents the number of branches in the proposal process I, we have that each unit can send l(2n-1) proposals.

The full specifications are provided below: Stable Allocation